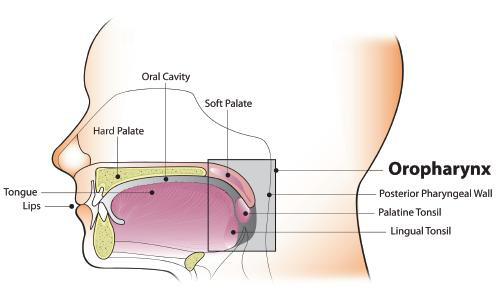

Oncogenic oral HPV infection is a major risk factor for oropharyngeal cancer, rather than oral cancer, per se.2, 17, 18, 27, 35, 36 HPV has emerged as an etiologic factor for OP-SCC of the tonsil and oropharynx,18, 35, 37 but not for the totality of tongue cancers.38, 39 Based on data from U.S. cancer registries, an estimated 71% of OP-SCC each year—or over 11,000 cases—are associated with HPV infection.40, 41 The vast majority (over 90%) of HPV-positive OP-SCC are associated with HPV-16, a high-risk, HPV subtype that is commonly associated with cervical cancer and other anogenital cancers.18, 37, 42, 43

Oropharyngeal cancer is now considered the most common cancer caused by HPV in the United States, with nearly 81 percent of OP-SCC cases classified as HPV-associated (between 2007 and 2015).44 Three analyses of U.S. cancer databases over two time periods (2013-2014 and 2017-2018) indicated that white, non-Hispanic men have higher incidences of oral cavity and pharyngeal cancers in the U.S.21, 45, 46 Another study found that the median age of individuals diagnosed with HPV-associated OP-SCC in the U.S. has increased to about 58 years of age, with a growing number of cases across all age groups, including older adults.47

Data suggest that oral HPV infection prevalence is lower in men and women who have received HPV vaccination than those who have not.48 Although it is possible that the HPV vaccine might also ultimately prevent OP cancers, as the vaccine prevents an initial infection with HPV types that can cause these cancers, current data are lacking regarding prevention of HPV-associated OP cancer.34 Clinical trials designed to answer these questions are currently underway.

HPV Vaccine

In 2020, the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) issued an updated policy statement on HPV vaccination49 as follows:

The AAPD supports measures that prevent [oral and oropharyngeal cancers], including the prevention of HPV infection, a critical factor in the development of oral squamous cell carcinoma.

The AAPD encourages oral health care providers to:

- Educate patients, parents, and guardians on the serious health consequences of [oral and oropharyngeal cancers] and the relationship of HPV to [oral and oropharyngeal cancers].

- Counsel patients, parents, and guardians regarding the HPV vaccination, in accordance with CDC recommendations, as part of anticipatory guidance for adolescent patients.

In October 2018, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a supplemental application for Gardasil 9® (HPV 9 valent-vaccine, recombinant; Merck & Co., Inc.) expanding the approved use of the vaccine to include women and men aged 27 through 45 years.50 Gardasil 9® was previously approved for use in males and females aged 9 through 26 years.

In 2020, Villa et al.

51 published an umbrella review of systematic reviews, summarizing evidence on the safety, efficacy, and effectiveness of HPV vaccines. The review compiled findings from 30 systematic reviews and found evidence that available HPV vaccines “are safe, effective, and efficacious against vaccine-type HPV infection and HPV-associated cellular changes, including precancerous and benign lesions.”