The challenges and rewards of volunteering abroad

Editor’s note: In February 1970, a group of dental students met in Chicago to form an independent national dental student organization and named themselves the Student American Dental Association (SADA). The following year the ADA embraced this idea and organized a meeting of student representatives from each dental school in the country to help form a new organization called the American Student Dental Association (ASDA). Although scattered all over the world, several of the founders and leaders of those two organizations planned on having a reunion this year in celebration of their 50th anniversary, but it was scuttled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, they decided to mark this auspicious occasion by writing and publishing a series of seven articles regarding the state of dentistry, dental education and health care in general from a retrospective perspective. The first two articles in the series were on licensure reform and were published in the July 14 and Aug. 24 issues of the New Dentist News . This is the fourth article of the series.

In the summer of 2003, I suddenly found myself confronting a profound sense of guilt. It had been 20 plus years since I left the faculty at the University of Pennsylvania in 1981 with a plan to set up a large group practice in the Philadelphia suburbs. Within two years I had established two facilities in large regional malls, and had devoted virtually all my time and energy to my patients and my practice. The time to give back to society in some shape or form was long overdue.

I decided that I wanted to do volunteer work of some kind, but it was a vague goal – a plan with no details. I had no idea how to proceed. What I did know was that my admiration for the work of Doctors Without Borders was a motivation to volunteer in a foreign country.

I contacted the ADA for information, and they proved to be a rich resource of information. I researched volunteer agencies with experience in placements abroad, and discussed my idea with several friends who had travel experience in Southeast Asia. They all raved about Thailand.

My business partner, Dr. Edward Basner, who had served as a dentist in the Air Force in Northern Thailand, loved his experience there, especially doing volunteer missions in the surrounding communities. He told me that the people there were warm, friendly and incredibly appreciative.

All roads pointed to Thailand even though I had never been there and quite frankly knew very little about the country.

Next, I contacted Dr. Barry Simmons, the founder of Dental Health International, who was widely considered the guru of volunteer dentistry abroad, and a true humanitarian. He had famously spent several months each year in the most remote areas around the world, by himself, transporting his own mobile instruments and custom-designed equipment at his own expense.

I visited him in Athens, Georgia, and his advice and encouragement was invaluable. He too had spent considerable time in northern Thailand and strongly recommended that I go there. We decided on a mobile dental outreach project for remote Hilltribe highland communities in the mountains of Chiangmai Province.

Chiangmai is the second largest of Thailand’s 77 provinces, and home to Chiangmai City, one of the oldest (circa 1296) and second largest city in Thailand. The Hilltribe people are actually nine different tribes of various ethnic origins who have resided in the high mountainous terrain for centuries, primarily as migratory subsistence farmers. They comprise approximately 13% of the Thai population, and are the largest group of non-Buddhists in the country.

But how was I going to make this happen?

An organization called Global Crossroad/Asia Volunteers helped me formulate my project and introduced me to a government hospital in Hangdong Township, and the dental school in Chiangmai.

In April 2004, I made my first trip to Chiangmai to meet with my contacts who would become my sponsors and friends – Dr. Wannasee, the dental director at Hangdong Hospital; Dr. Wirat, the dean of the dental school; and Dr. Kumkom, the chairwoman of community Dentistry. Fortunately, they all spoke English very well. They informed me that the hospital and dental school had already established their own mobile outreach initiatives, and all I had to do was customize them to my needs and join in. What would be unique however was that it would be the first time that a foreign dentist worked with them, shoulder-to-shoulder, out in the field.

I returned in December for my initial three-week project. I was informed that Dean Wirat had made a special trip to the dental board in Bangkok to secure a temporary dental license for me, a detail that I hadn’t even considered.

Hangdong Hospital arranged for the locations, coordinated with the locals for the dates, provided transport for all the equipment and instruments (on flat-bed, four-wheel drive trucks), brought technicians to set-up, hook-up, and service the mobile equipment on site, set up the open-air “operatories” and all the sterilized and bagged instruments on trays, and made sure that the word got out that we were coming to provide free dental care to anyone who needed it.

Schools in the area transported their kids on the back of pickup trucks and many of the locals would arrive on motorbike and just walk-in. The hospital staff screened and triaged the patients and placed them in a queue. I would work alongside three of the hospital dentists and four dental nurses, who also served as my translators.

We serviced three remote villages, using on-site health centers for water and electric hookups and operating space, and saw hundreds of patients, mostly kids, doing mostly extractions and simple fillings. The amount of severe decay that I witnessed was quite an eye-opening experience.

The second phase of the project was organized by the dental school, which had a mobile clinic/bus. I accompanied their staff on two outreach projects to rural health centers, once again providing mostly oral surgical services. We also went to three rural schools in the area to give out toothbrushes, toothpaste, provide good oral health education, do dental screenings and onsite extractions for those kids who had infection and pain.

It was my first time performing dentistry in the field without the benefit of X-rays. I learned to accept it as a fact of life that was required under the circumstances; a compromise that was needed to provide relief of pain and infection to people who had little or no access to dental care.

This turned out to be a great life-changing experience for me. The people I met and worked with were welcoming, friendly, incredibly helpful, and appreciative of my participation. In March 2005, I returned for what would prove to be my final volunteer mission. My project ended when my sponsors Dean Wirat retired and Dr. Kumkom went on sabbatical.

I returned to Philadelphia, decided to retire, sold my dental practice, and moved permanently to Thailand in September 2005 to live in Hangdong – the place I had never even heard about before my trip the previous year. I have lived happily here ever since.

For those who might be considering volunteering abroad, here are my suggestions and tips:

- It can be a dangerous world out there – find a safe place and carefully research your choices. Of course, for many Americans who only speak English, an English-speaking destination is probably preferable, but not required. It’s best not to attempt to do this strictly on your own. Find a reputable volunteer placement service to help you, even if there are fees involved.

The ADA provides a valuable guide to international volunteer resources and a database of programs that you should check out: http://internationalvolunteer.ada.org - You will need to secure necessary visas and provide proof of vaccinations if they are required, and make sure your passport is valid for at least six months beyond your return. It’s a good idea to obtain an official letter of introduction from your sponsors in case there are any questions at Immigration & Customs when you arrive at your destination.

- Once you have settled on your venue, it would be most prudent, if feasible, to organize a preliminary “scouting mission” to introduce yourself, personally cultivate local contacts and resources, and confirm and finalize the operational details of your project. Undoubtedly, there will be surprises and unanticipated glitches to deal with, but a preliminary visit should help to keep them to a minimum.

- A clinical project obviously requires instruments, equipment, sterilization, and a million other things – an almost impossible task to manage by yourself in a foreign country unless you are a Barry Simmons, who is a one-in-a-million. I was fortunate to fall into pre-existing outreach programs, with local clinicians and administrators who maintained ongoing responsibility for quality assurance, continuity, patient follow-up, and sustainability - essential features for any volunteer project. They welcomed my participation and helped me to integrate into their systems and protocols. Thankfully, all of the myriad of details were already provided, which enabled me to focus on my role as a field clinician. In looking back, I think that this was an ideal situation – one that I highly recommend if you can find it.

- Last, but not least, you will need to find out about dental licensure requirements, even for volunteering, in your host country. Institutional licensure and temporary licensure are two of the most common methods. However, many countries are so in need and appreciative that it may simply be a non-issue.

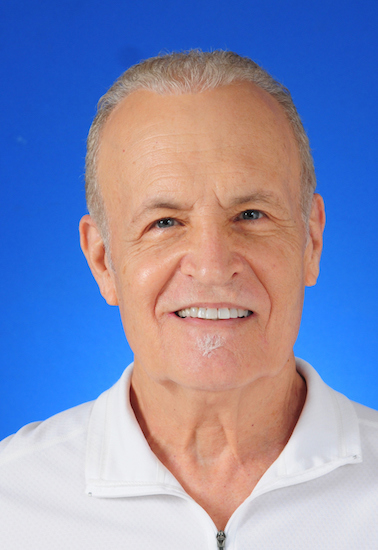

Dr. Nash was ASDA’s first chair of dental licensure reform from 1971–72. He graduated from New York University College of Dentistry in 1971 as valedictorian of his class. After graduation he completed a one-year general practice residency at Brookdale Hospital in Brooklyn, N.Y, and a three-year postdoc in medical behavioral science at the University of Kentucky Medical School. In 1976 he joined the faculty at the University. of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine as the director of the DAU/TEAM Program. In 1981 he founded Century Dental Centers, an interdisciplinary group practice in the Philadelphia suburbs. He remained in private practice until 2005 when he retired and moved to Chiangmai, Thailand, where he currently resides with his wife Walaporn.