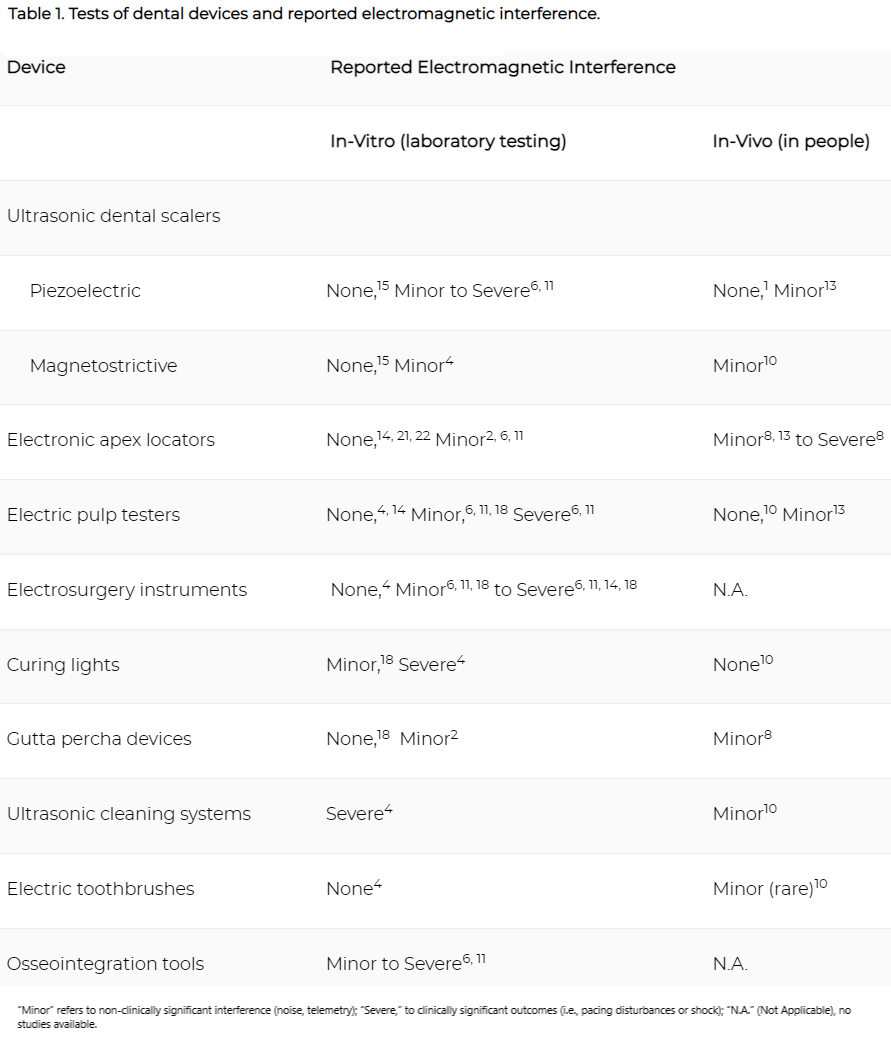

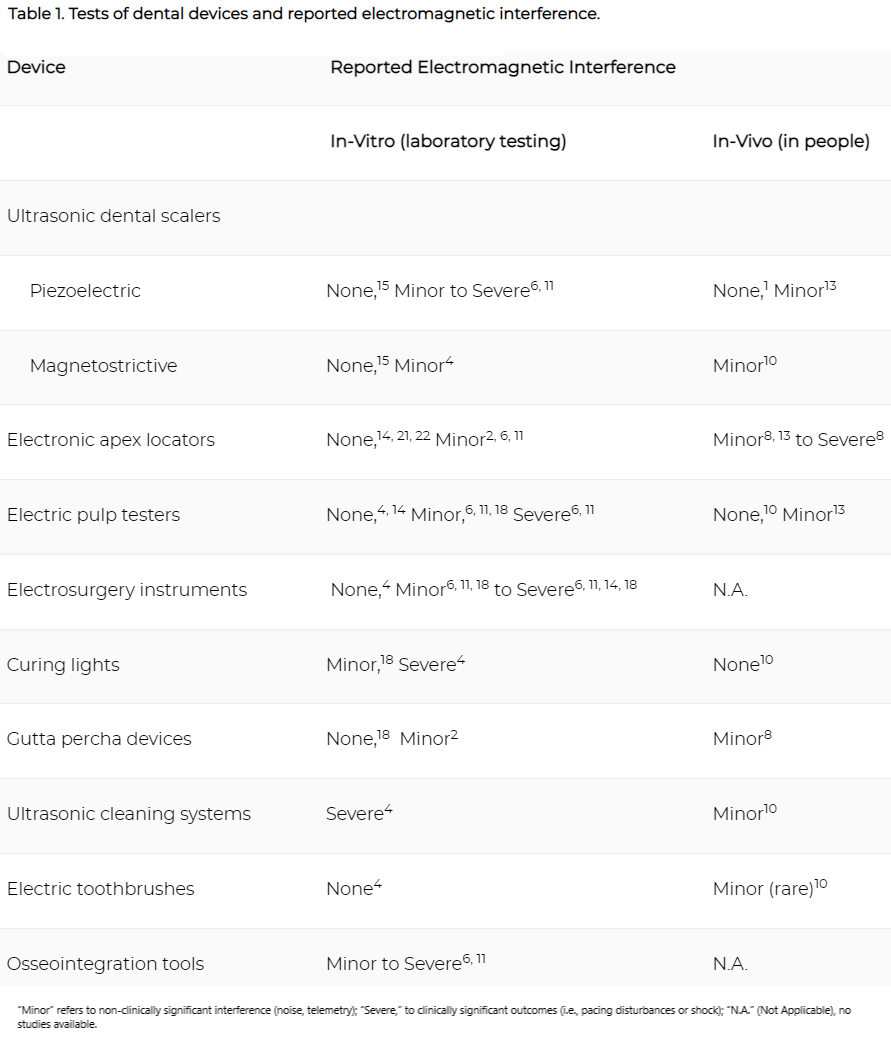

Various types of tested electronic dental devices have shown some potential for causing electromagnetic interference in CIEDs (Table 1). However, there is conflicting evidence, and most of the positive results come from in-vitro studies. Some researchers claim that human tissue provides shielding and other protection from electromagnetic interference that cannot be replicated in a laboratory setting.2, 6, 16 Various instruction manuals for electronic dental devices discourage use of these devices with patients who have CIEDs,1, 19, 24 but other researchers attest that newer CIEDs are designed to lower the risk of interference from electromagnetic sources.6 While some researchers claim that clinical interference from ultrasonic dental devices is “highly improbable,”24 the theoretical possibility remains. A number of studies mention the increasing likelihood of electromagnetic interference if a device comes within 37.5 cm (~15 inches) of the CIED or lead wire.3, 7, 25

A 2015 in-vivo prospective cohort study15 exposed 32 patients with CIEDs to a magnetostrictive scaler, an ultrasonic cleaning system, a curing light, electric toothbrush, and battery-operated pulp tester. The study found minor electromagnetic interference when the scaler and cleaning system were less than 18 inches from CIED leads.15 Other asymptomatic minor interactions occurred with other devices at smaller distances but appeared to be interference with the monitoring devices (telemetry) and not the pacing or functioning of the CEID itself.15 Several studies have cited these interactions with telemetry and device monitoring as evidence of electromagnetic interference associated with dental equipment use.5, 15, 28, 29

There is evidence that piezoelectric scalers (commonly used in Europe) are safer than magnetostrictive devices1, 24, 25 and may pose no risk to patients with CIEDs.4, 17, 18, 25, 30 Several in-vitro studies4, 6, 16 present some evidence of electromagnetic interference by magnetostrictive scalers, whereas a 2013 in-vivo study reported no interference between piezoelectric scalers and 5 different implantable cardioverter-defibrillator types in 12 patients.1 A 2018 in-vivo study of piezoelectric scalers found only minor interference (noise) in telemetry, and no adverse events in pacemaker function.18

Apex locators and osseointegration monitoring tools have been found in in-vitro tests to be a low risk for light electromagnetic interference.2, 16 However, in one in-vivo study, a symptomatic interruption of pacing was induced in patients by two brands of apex locators.13 A 2018 in-vivo study of an apex locator found only minor telemetry interference in 3.3% of patients.18

Although pulp testers were shown to be associated with “severe” electromagnetic interference (stimulation inhibition or inappropriate discharge) in in-vitro studies from 2015 and 2016,6 a number of other in-vitro studies found no interference,4, 15, 19, 27 nor was interference found in a 2015 in-vivo study.10 A 2018 in-vivo study found minor interference in telemetry in 7.5% of patients.18

Electrosurgical units are used to remove and cauterize tissue, and are available as monopolar (which requires an electrical current to pass through the patient’s body) and bipolar (in which the current is completed between two electrodes at the device tip) devices. In-vitro studies have consistently shown clinically significant electromagnetic interference to CIEDs from monopolar electrosurgery, including pacing interruptions and electrical shock.6, 19, 27 The Heart Rhythm Society/American Society of Anesthesiologists published a consensus statement on management of CIED patients, which states that “[m]onopolar electrosurgery is the most common source of [electromagnetic interference] and CIED interaction in the operating room,”31 and that head and neck region electrosurgeries using monopolar equipment “pose more of a risk for oversensing and damage to the CIED system.”31

Battery-operated curing lights were shown to induce pacing inhibition in a 2010 in-vitro study,4 but more recent studies from 201515, 27 did not report any electromagnetic interference from curing lights. Ultrasonic cleaning systems were shown to produce significant electromagnetic interference in the 2010 study,4 and while minor interference with telemetry was encountered in the 2015 in-vivo study, pacing or sense functions were not affected.15 Both the 2010 and the 2015 studies found little or no risk from electric toothbrushes.4, 15

Gutta-percha heat carriers, but not gutta-percha guns, have been shown to produce electromagnetic interference in the form of background noise,2, 13 as well as cause an asymptomatic pause, as demonstrated in a 2015 in-vivo study.13 However, a 2015 in-vitro study found no interference between gutta-percha devices and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators.27