Wellness Resources

When you focus on your mental health, you can deliver the best dental health for your patients. Use these tools to take care of your well-being.

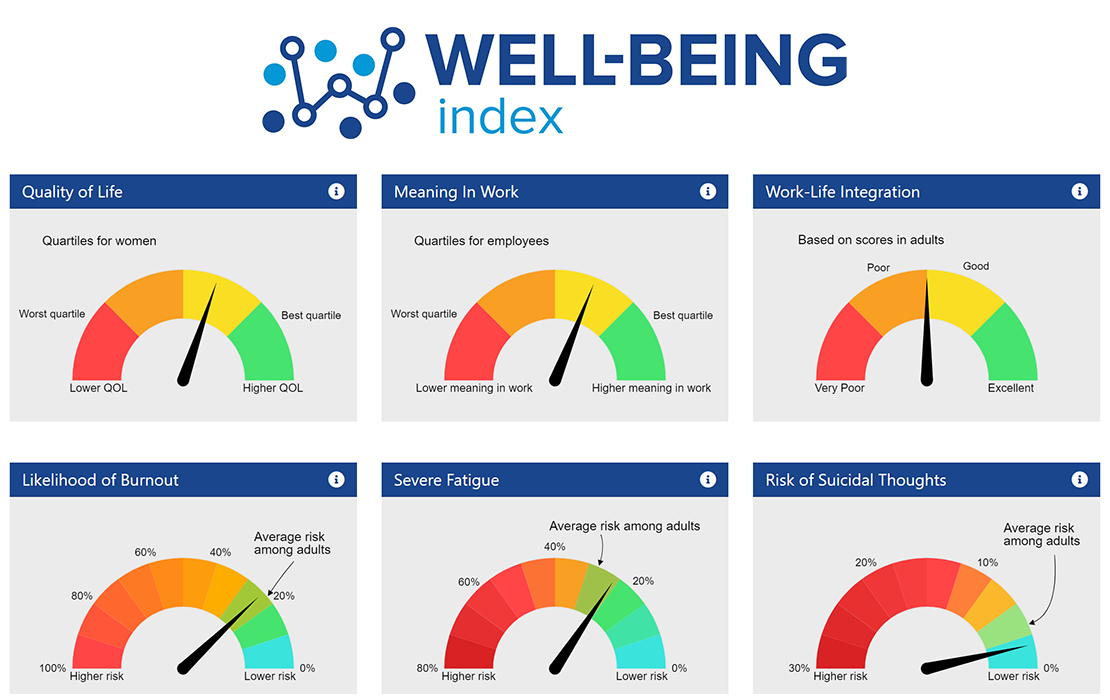

Assess Your Well-Being

Assess your levels of well-being with this anonymous, validated Mayo Clinic tool.

Act to Improve Your Well-Being

If you or someone you know is experiencing suicidal thoughts or a crisis, please text or dial 988 to be connected to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. This service is free and confidential. For a medical emergency dial 911.

More than 82% of dentists report feeling “major” stress about their careers. Reduce burnout, support colleagues and find well-being programs in your state.

Practice without pain. Use these resources to prevent and minimize the physical aches that come with dentistry.

Advocate for the Profession

The ADA works advance the profession’s health and wellness on personal, local, state and national levels. See how below.